By TheOneLawFirm.com Contributors

“I wasn’t in the room. I didn’t pull the trigger. But here I am—for life.”

— Pamela Smart, in a 2020 prison interview

In the spring of 1990, Pamela Smart was a 22-year-old media coordinator at a high school in New Hampshire. By summer’s end, she was a household name, accused of manipulating her teenage lover into murdering her husband. Her trial—broadcast live in a courtroom brimming with cameras and controversy—became America’s first made-for-TV courtroom drama. But beyond the true-crime spectacle lies a case that fundamentally reshaped criminal law practice in four domains: media influence, evidentiary boundaries, sentencing disparities, and the razor-thin line between law and politics.

More than three decades later, State v. Smart, 259 A.3d 1271 (N.H. 2021), remains a cautionary tale and a procedural landmark. From the use of undercover recordings before indictment to the limits of judicial review over clemency, the Smart case has left a long shadow over how high-profile defendants are tried—and how they serve their time.

| Element | Details |

|---|---|

| Court | New Hampshire Supreme Court |

| Defendant | Pamela Smart |

| Charges | Accomplice to first-degree murder, conspiracy, and witness tampering |

| Conviction Date | March 1991 |

| Sentence | Life in prison without parole |

| Key Appeal Ruling | 259 A.3d 1271 (N.H. 2021) (commutation petition dispute) |

| Final Outcome | Sentence upheld; commutation hearing denied without judicial review |

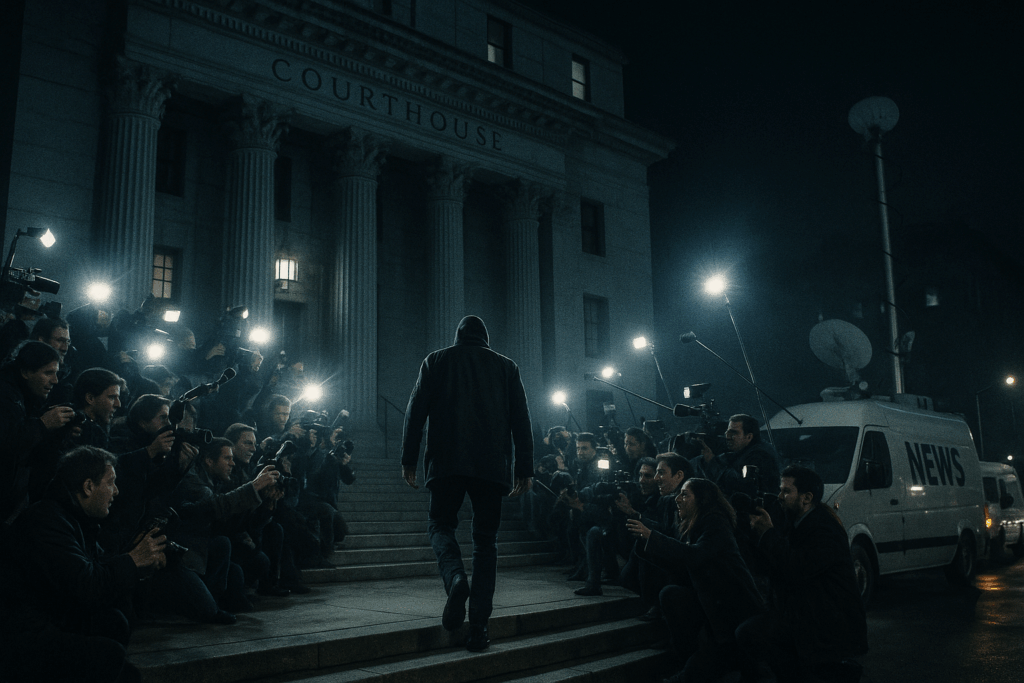

When Court TV broadcast the entire trial of Pamela Smart in 1991, it became a media sensation. Viewers were glued to the tale of a young wife and her affair with a 15-year-old student, Billy Flynn, who ultimately confessed to shooting Smart’s husband, Gregg.

The defense argued that the media frenzy poisoned the jury pool. On appeal, however, the New Hampshire Supreme Court found that the coverage—while widespread—was “factual” rather than “inflammatory.” The Court ruled that not all pretrial publicity constitutes constitutional prejudice. Crucially, Smart’s attorneys never requested a trial delay or change of venue. The takeaway? A defense lawyer’s failure to formally challenge media saturation waives the argument later. Prejudice from publicity isn’t presumed unless it’s egregious—and even then, procedural moves matter more than complaints after the fact.

“Trial by media” may be dramatic, but Smart reminds lawyers: only the trial record can overturn a verdict.

When Cameras Roll, Is Justice on Pause?

When Cameras Roll, Is Justice on Pause?The Smart trial opened the floodgates to televised proceedings. But was it fair?

Defense counsel later claimed that courtroom cameras created a “circus atmosphere” that undermined the integrity of the trial. But the appellate court wasn’t convinced. The trial judge had maintained order, and there was no evidence the jury was affected by the presence of cameras. This was consistent with Chandler v. Florida, the U.S. Supreme Court case that said cameras don’t inherently violate due process.

Smart’s legacy here is subtle but powerful: courts now presume that media presence is permissible—unless you can prove it directly tainted the jury or disrupted decorum. Today’s criminal attorneys must navigate a legal landscape where courtroom transparency is the default, and objections must be backed by evidence, not emotion.

After the murder, Smart’s teenage accomplices began cooperating with police. One of them, a 16-year-old friend named Cecilia Pierce, agreed to wear a wire. Over the course of several conversations, Smart made statements suggesting she knew more than she claimed. Those tapes were the smoking gun.

Smart’s team argued that she had retained a lawyer and told police not to speak to her without counsel. Shouldn’t that have prevented the secret taping?

Not quite. The New Hampshire Supreme Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment right to counsel hadn’t yet “attached,” because Smart hadn’t been indicted or taken into custody. In the eyes of the law, the recordings were fair game. The decision mirrors federal precedent: unless you’re under arrest or formally charged, police can still lawfully gather evidence—even through your friends.

For attorneys, the Smart case is a brutal reminder: clients must be warned that anything they say—ever—can and will be used against them. Even before formal charges. Even to a trusted friend.

Perhaps the most bitter pill for Smart was watching her co-conspirators walk free. Billy Flynn—the shooter—served 25 years before being paroled. His three teenage accomplices also struck deals and are now out.

Smart, who went to trial and maintained her innocence, received life without parole.

It’s a textbook example of the sentencing disparities that riddle the American justice system. Cooperation with prosecutors led the actual triggerman to freedom, while the alleged mastermind remains incarcerated indefinitely. The term “trial penalty” looms large: go to trial, risk everything. Plead, and you might see daylight.

The real murderer got parole. The woman who didn’t pull the trigger got a life sentence.

For prosecutors, the case affirms the power of leverage. For defense attorneys, it raises the agonizing question: when does innocence cost too much?

By 2021, Smart had served over 30 years in prison. She had earned two master’s degrees, become a mentor to other inmates, and petitioned the state for clemency—asking for the possibility of parole.

The Governor and Executive Council refused to even hold a hearing.

Smart’s legal team challenged this decision in court, arguing it was arbitrary. The New Hampshire Supreme Court disagreed. The ruling: clemency is a political question, not a legal one. Courts cannot force the executive to hear, review, or justify its decision. For inmates serving life without parole, this is a chilling precedent. The only remaining path to freedom lies through the narrowest of gates—one that the courts cannot compel open.

| Area | Legal Practice Implication |

|---|---|

| Media & Publicity | Publicity alone doesn’t invalidate a trial unless defense formally challenges it pre-trial. |

| Cameras in Court | Cameras are allowed unless there’s actual disruption or documented prejudice. |

| Evidentiary Rules | Undercover recordings are admissible pre-indictment; right to counsel attaches later. |

| Sentencing Strategy | Trial can lead to harsher penalties than cooperation—manage client expectations carefully. |

| Clemency Limits | Courts won’t intervene in executive clemency denials—advocacy must shift outside the courts. |

State v. Smart has become more than a tragic story or a media milestone—it’s now part of the procedural DNA of criminal law. From voir dire strategy to pre-charge evidence gathering, from the perils of public trials to the limits of post-conviction relief, the Smart case is essential reading for any legal professional navigating high-stakes criminal litigation.

Because sometimes the biggest lessons come from the smallest jurisdictions.

State v. Smart, 259 A.3d 1271 (N.H. 2021).

State v. Smart, 136 N.H. 639 (1993).

Petition of Smart, 175 N.H. 656 (2023).

Chandler v. Florida, 449 U.S. 560 (1981).

Associated Press, “Pamela Smart’s Clemency Denied Again,” Mar. 2022.

New Hampshire Public Radio, “Pamela Smart Asks for Sentence Reduction Hearing,” Jan. 2021.

First Circuit Court of Appeals, Smart v. Spencer, 2004 WL 3444786 (1st Cir.).

Smart’s clemency materials and public statements compiled by FreePamSmart.org.

Legal commentary: D. Ross, “The Sixth Amendment’s Outer Limits: When Counsel Attaches,” N.H. Bar Journal, 2022.

L. Abrams, “Trial by Television: The Smart Case and the Rise of Courtroom Media,” Harvard CRCL Review, 2023.