On the last day of the Supreme Court’s 2023 term, a controversy over a wedding website that didn’t even exist set a pivotal precedent. In 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis, a Colorado web designer who had never made a same-sex wedding site – and in fact had never been asked to – won the right to refuse such work on free speech grounds. The Court’s decision, a 6–3 ruling, has been hailed as a major victory for First Amendment protection of expressive businesses and decried as a setback for LGBTQ+ rights. Beyond the culture war headlines, this landmark case raises profound questions for constitutional law practitioners and the future of anti-discrimination laws in the marketplace. How did a hypothetical scenario become a constitutional earthquake, and what does it mean for lawyers, businesses, and protected classes going forward?

A Clash of Rights at the High Court

Crowds of supporters and opponents rally outside the U.S. Supreme Court as the justices hear arguments in 303 Creative v. Elenis, a case pitting free speech against LGBTQ anti-discrimination protections. Both sides carried signs – from rainbow-colored pleas of “Our Rights Are Not Up for Debate” to banners declaring “Free Speech is for Everyone.”

The case began when Lorie Smith, owner of 303 Creative LLC, sought to expand her custom web design business to include wedding websites – but only for heterosexual weddingsscotusblog.comen.wikipedia.org. A devout Christian, Smith believed that creating websites celebrating same-sex marriages would contradict her faith. She even planned to post a notice on her own site explaining that she “will not be able to create websites for same-sex marriages” due to her religious convictionsen.wikipedia.orgfirstamendment.mtsu.edu. This plan ran headlong into Colorado’s Anti-Discrimination Act (CADA), which prohibits businesses open to the public from denying services based on sexual orientation and from announcing any such discriminatory policyfordharrison.comfirstamendment.mtsu.edu. In Colorado (as in roughly half of U.S. states), a public business cannot say “We don’t serve your kind” – whether in action or in advertisingscotusblog.comscotusblog.com.

Fearing punishment under CADA, Smith launched a pre-enforcement lawsuit in 2016, essentially asking courts: can Colorado force me to create speech that violates my beliefs? This question arrived at the Supreme Court as a pure clash between free speech and equality laws, without any specific customer dispute. (In fact, when an inquiry from a same-sex couple mysteriously appeared in Smith’s inbox, reporters later found that the inquiry was likely fabricated – the named “client” was a straight man who never sent it. Regardless, the case proceeded on stipulated facts aloneen.wikipedia.orglawcommentary.com.) By taking up this hypothetical dispute, the conservative-majority Supreme Court signaled its readiness to answer a thorny constitutional question left open since the Court’s 2018 Masterpiece Cakeshop decision: Can the state compel an artist or creative professional to express a message they disagree with, as the price of doing business?scotusblog.comcbsnews.com

What the Supreme Court Decided

In 303 Creative, the Supreme Court answered with a resounding “No.” The majority held that Colorado’s law, as applied to a custom wedding website designer, violated the First Amendment. Writing for the 6–3 majority, Justice Neil Gorsuch declared that the government cannot “force an individual to speak in ways that align with its views but defy her conscience about a matter of major significance.”scotusblog.com In plainer terms: designing a bespoke wedding website is a form of pure expressive conduct – the designer’s own speech – and the state compelling her to design one for a same-sex wedding would amount to compelled speech, which is strictly forbidden by the Constitutionfordharrison.comfordharrison.com.

“The First Amendment envisions the United States as a rich and complex place where all persons are free to think and speak as they wish, not as the government demands.” – Justice Neil Gorsuch, writing for the Courtcbsnews.com

Colorado had argued that its Anti-Discrimination Act regulates commerce, not speech, simply requiring businesses to serve all customers equally. But the Court disagreed: if the service in question is inherently expressive, then requiring its creation on demand – regardless of message – is an intrusion on free speech. The majority noted that there is a virtually limitless market of ordinary goods and services (from hotel rooms to hamburgers) that no one would consider “speech” protected by the First Amendmenten.wikipedia.org. However, custom expression – like the artistic design of a wedding website – falls squarely under First Amendment protection. Forcing a creative professional to produce a message they object to, the Court held, “is an impermissible abridgment of the First Amendment’s right to speak freely.”cbsnews.com

Hypotheticals and the “Slippery Slope”

Throughout its opinion, the majority stressed that this case was about message, not status. Lorie Smith, they emphasized, was willing to serve LGBT clients – she would, for example, happily design graphics for a gay client’s business – so long as the content of the project did not celebrate same-sex marriagefordharrison.com. What she objected to was the message (a wedding website endorsing a marriage contrary to her beliefs), something she would refuse to create for any client, gay or straightyalelawjournal.orgyalelawjournal.org. In the majority’s view, Colorado wasn’t protecting LGBTQ citizens from unequal service so much as “eliminating ideas that differ from its own” about marriageyalelawjournal.orgyalelawjournal.org. To drive this point home, Justice Gorsuch – echoing a lower court dissent – trotted out a parade of chilling hypotheticals:

“Governments could force ‘an unwilling Muslim movie director to make a film with a Zionist message,’ compel ‘an atheist muralist to accept a commission celebrating Evangelical zeal,’ or require a gay website designer to create websites for an organization advocating against same-sex marriage.”scotusblog.com

These scenarios, the Court suggested, illustrate the danger of Colorado’s position. If the state can compel Smith’s speech, what principled limit would stop it from compelling anyone’s speech on any subject, in the name of non-discrimination? The First Amendment, Gorsuch wrote, protects speakers from such intrusions, even if the speech in question is “deeply misguided” or likely to cause “anguish” to others. In a free society, tolerance must cut both ways: just as the government cannot censor pro-LGBTQ expression, it also cannot force individuals to voice messages celebrating same-sex marriage when it violates their consciencescotusblog.comcbsnews.com.

Notably, the ruling explicitly extended First Amendment protection to other creative professionals. The majority assured that artists, writers, and other “speakers” for hire are shielded from being conscripted to spread messages they rejectscotusblog.comlawcommentary.com. A wedding singer cannot be forced to croon a song with offensive lyrics; a film studio run by animal rights activists need not produce a commercial extolling fur coats. By the same token, the Court reasoned, Lorie Smith cannot be forced by Colorado to craft a website celebrating a same-sex union.

The Dissent: “No Right to Refuse Service”

The Dissent: “No Right to Refuse Service”

In a fiery 38-page dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor (joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson) accused the majority of mischaracterizing the facts and stakes. To the dissent, what Smith sought was not just the freedom to decline a particular message, but a constitutional exemption to refuse a service to an entire class of people. “The Constitution contains no right to refuse service to a disfavored group,” Sotomayor wrote bluntlylawcommentary.com. Framing the case in stark terms, she opened: “Today, the Court, for the first time in its history, grants a business open to the public a constitutional right to refuse to serve members of a protected class.”lawcommentary.com

The dissenters did not dispute that compelled speech is unconstitutional; in fact, both sides agreed that if Colorado truly forced Smith to publish a specific message affirming same-sex marriage, that would violate the First Amendmentyalelawjournal.orgyalelawjournal.org. But in Sotomayor’s view, that’s not what Colorado’s law does. CADA doesn’t dictate or approve the content of wedding websites – it simply says if you offer wedding website design services, you must offer them to all customers regardless of sexual orientationscotusblog.com. Smith, in other words, remains free to decide what content to include in her sites (she could, for instance, decline to include any particular poems or Bible verses she dislikes) – she just cannot refuse to make the same standard website for a gay couple that she would make for a straight couplescotusblog.comlawcommentary.com. The dissent saw no meaningful difference between this case and the countless scenarios where businesses must follow anti-discrimination laws: a motel owner with racist beliefs can’t refuse to rent rooms to Black travelers even though hosting someone could be seen as “expressing” approval of them; a caterer who personally disapproves of interfaith marriage can’t refuse to serve a Jewish-Christian wedding just because their presence might imply support. In short, offering a service to the public comes with the obligation to serve all on equal terms.

Justice Sotomayor warned that the decision opens the door to broad discrimination masquerading as free expression. If a web designer can refuse gay couples, what stops an interior decorator or a portrait photographer from doing the same, under the claim that their work is “expressive”?en.wikipedia.org “Stationers, photographers, even jewelers and tailors” could all be newly empowered to turn away LGBTQ clients, she cautioned, under the majority’s logiclawcommentary.comen.wikipedia.org. The dissent famously lamented: “This decision gives a green light to the ‘permission to discriminate’. The immediate, symbolic effect is to mark gays and lesbians for second-class status.”scotusblog.comlawcommentary.com In a poignant passage, Sotomayor wrote that the ruling’s message was as clear as a sign in a shopwindow: “Some services may be denied to same-sex couples.”cbsnews.com

Majority vs. Dissent: Two Different Visions

To better understand the split, it’s helpful to compare the majority and dissent side by side:

| Majority (Gorsuch) – Free Speech Focus | Dissent (Sotomayor) – Equal Service Focus |

|---|---|

| Core View: Government cannot compel speech that a person “would not otherwise make” as part of their businessen.wikipedia.org. Forcing Smith to create a gay wedding website compels her expression and “abridges the First Amendment”. | Core View: Business has no right to turn away customers based on identity. Colorado law does not compel any specific speech, only that if you serve wedding clients, you serve all regardless of sexual orientationscotusblog.com. |

| What Law Does: Targets message, not status. Smith objects to what is being expressed (a same-sex marriage celebration), not who is requesting ityalelawjournal.orgyalelawjournal.org. Colorado’s true aim was to “eliminate ideas” it dislikes (traditional view of marriage) by compelling speech endorsing same-sex marriageyalelawjournal.orgcbsnews.com. | What Law Does: Prevents status-based discrimination. Smith was asked to provide the same service she offers to others. The law doesn’t force any particular words on her websitesscotusblog.com – she can design sites with Biblical themes or without certain texts, as long as she doesn’t refuse service to gays as a classlawcommentary.com. |

| Scope: Applies to expressive, custom services. The Court noted “innumerable goods and services” (hotels, restaurants, transportation) are not expressive and so anti-discrimination laws easily apply thereen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. But artists, writers, musicians, designers and others who speak for a living are protected from coercionscotusblog.com. | Scope: Undermines public accommodations laws. Anti-bias laws have long co-existed with the First Amendmentfordharrison.com. The majority doesn’t formally overturn precedents upholding such laws (e.g., requiring Jaycees clubs to admit womenfordharrison.com or barring whites-only business policiesfordharrison.com), but its logic could erode those protections. The dissent fears a broad license to discriminate under the banner of “expression”lawcommentary.comfordharrison.com. |

| Limitations: Not a blanket endorsement of discrimination. The majority called it “pure fiction” that their ruling would allow, for example, restaurants to hang “whites only” signs or law firms to deny female partnersfordharrison.com. “Context matters,” Gorsuch wrote – laws that incidentally affect expression in regulating non-expressive goods are different from laws that “compel speech” directlyfordharrison.comfordharrison.com. | Consequences: Sets a historic precedent: this is the first time the Court has ever sanctioned a constitutional right to refuse service in businesslawcommentary.com. It risks re-segregating the marketplace on religious or ideological lines. The dissent points out that even at the height of Jim Crow, the Court in Runyon v. McCrary (1976) rejected a private school’s claimed right to exclude Black children as a matter of “free association”fordharrison.com. The fear is that 303 Creative emboldens new forms of exclusion. |

While the two opinions talked past each other at times, both insisted their opponent’s fears were overblown. Gorsuch argued that Smith’s stance is no license to discriminate in general, because she serves “all people” (including LGBTQ customers) and only refuses certain messagesfordharrison.comscotusblog.com. Sotomayor retorted that the difference between refusing a gay couple and refusing to make a gay wedding website is illusory – in practical terms, a gay couple is turned away because of who they arescotusblog.comlawcommentary.com. As one legal commentator observed, the majority and dissent were “ships passing in the night,” each addressing a different questionyalelawjournal.orgyalelawjournal.org. The majority saw 303 Creative as a compelled-speech case; the dissent saw it as a discrimination case. Depending on which frame you accept, you reach opposite conclusions – and that divergence now defines the law’s new fault line.

Fallout: Free Speech or “License to Discriminate”?

Reactions to the decision reflected this schism. Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), the conservative advocacy group that represented Smith, hailed 303 Creative as a “victory for free speech”. “The government can’t force Americans to say things they don’t believe,” said ADF’s general counsel, praising the Court for reaffirming that “disagreement isn’t discrimination.”scotusblog.comcbsnews.com On the other side, civil-rights organizations like the ACLU and Human Rights Campaign decried the ruling as the Court giving businesses a “license to discriminate” against LGBTQ peoplecbsnews.comen.wikipedia.org. “A sad day in American constitutional law,” lamented Justice Sotomayor in her dissent, a line echoed by activists worried about the decision’s symbolic stingscotusblog.com.

Colorado officials warned that the ruling “threatens to destabilize our public marketplace”, cautioning that all kinds of businesses may now claim a free-speech right to selectively refuse customersscotusblog.com. Colorado’s Attorney General noted that while the state will “work hard to enforce our anti-discrimination laws within the confines of the Court’s opinion,” there is concern unscrupulous actors will stretch 303 Creative to justify new forms of biasscotusblog.com. Indeed, one of the biggest looming questions is how far the ruling reaches beyond wedding vendors. The majority tried to cabin its decision to “unique” expressive servicesen.wikipedia.org, but lines are already blurring. For example:

-

Photographers & Videographers: Many believe 303 Creative clearly covers them, since courts (and even Colorado in this case) agree photography and filming are artistic expressions. (Even before this ruling, some courts sided with wedding videographers who claimed a free speech right to decline same-sex ceremonies.)

-

Bakers & Florists: These were at the heart of earlier cases (like Masterpiece Cakeshop). Are custom wedding cakes and floral arrangements “expressive” enough to merit First Amendment protection? The Court didn’t explicitly say. Now, we can expect renewed litigation to test whether a cake designer’s work is more like art (protected) or more like catering (not protected).

-

Web Platforms & Tech Services: What about a freelance graphic designer asked to create a Pride Month logo, or a musician asked to perform at an event contrary to their beliefs? By analogy, 303 Creative suggests they cannot be compelled. But what about a larger business – say, a social media company run by religious owners who want to ban posts about same-sex weddings? The ruling doesn’t directly address corporate policies or big firms, but creative entrepreneurs are studying its language closely for potential leverage.

Even President Joe Biden weighed in, saying the decision “undermines basic truths” about equality. “In America, no person should face discrimination simply because of who they are or who they love,” Biden said, warning that the ruling could lead to more overt exclusion of LGBTQ Americans despite its ostensibly narrow scopecbsnews.comcbsnews.com. The political and social reverberations have been intense, but the legal community is now grappling with practical implications: How should lawyers advise clients in light of this ruling? And how will courts apply it in future cases?

Implications for Lawyers, Businesses, and Constitutional Law

For attorneys working in constitutional law (and savvy business owners), 303 Creative is more than a headline – it’s a signal of how this Supreme Court is recalibrating the balance between free speech and anti-discrimination norms. Here are several key implications and open questions:

-

A New Test for “Expressive” Businesses: The ruling protects a business only if it is selling custom expressive content. But what counts as expressive? The Court consciously avoided drawing a bright line, saying “what qualifies as expressive activity… can sometimes raise difficult questions”en.wikipedia.org. Moving forward, litigation will likely focus on whether a product or service is expressive (covered by 303 Creative) or non-expressive (still fully subject to anti-discrimination laws). Lawyers representing businesses may try to characterize services as artful or custom to invoke First Amendment protection; conversely, civil rights advocates will emphasize the commercial, routine aspects of a service to keep it under public accommodations laws. Expect disputes over wedding cakes, flower arrangements, invitation calligraphy, photography, and beyond – each testing the boundaries of expression.

-

Message vs. Status – Proving the Motivation: 303 Creative draws a theoretical distinction between refusing a message and refusing a customer. In practice, though, that line can be murky. Going forward, when a business refuses someone, courts might probe: Is the business truly objecting to the specific requested content, or just to the person or group? Savvy businesses will take a page from Lorie Smith’s playbook – craft policies that focus on the content (“We do not create messages that contradict Biblical marriage”) rather than outright banning a group (“No same-sex couples served”). Lawyers will likely advise clients to document consistent standards about what messages they won’t express (ideally applying them to all customers). At the same time, plaintiffs and enforcement agencies may look for evidence that a policy is a pretext for bias. If, for instance, a wedding photographer says “I just won’t shoot same-sex ceremonies because of the message,” but has a history of delivering every client exactly what they want (suggesting it’s about the couple, not any particular “message”), that could invite legal challenges. This dynamic puts attorneys in the role of delineating sincere speech objections versus discrimination, a task that will require careful factual development in each case.

-

Not a Blank Check for Bias: Importantly, the 303 Creative decision itself (and even more so, the Supreme Court’s public messaging) insists it is not an overarching rollback of civil rights lawsfordharrison.comfordharrison.com. Lawyers should note that the majority took pains to uphold past precedents where anti-discrimination laws were applied in non-expressive contexts. Cases like Roberts v. Jaycees (1984) and Hishon v. King & Spalding (1984), which forced organizations to include women, and Runyon v. McCrary (1976), which barred a private school from excluding Black students, remain good lawfordharrison.comfordharrison.com. The 303 Creative ruling distinguishes those cases by saying “very different considerations come into play” when a law is used to compel speech or expressive association on a matter of convictionfordharrison.comfordharrison.com. The upshot: businesses that sell non-expressive goods and services are unaffected – a restaurant cannot suddenly refuse to serve a gay couple dinner by claiming “culinary art is speech,” nor can a retail shop turn away customers because of race or religion. Such blatant discrimination still violates the law, and the Court explicitly rejected comparisons between Smith’s case and scenarios like posting a “White Applicants Only” job sign or excluding women from partnershipsfordharrison.comfordharrison.com. Lawyers on both sides should be careful not to over-read the ruling. As one civil rights attorney noted, 303 Creative is a “mixed bag” – it protects unique, custom artistic enterprises, but leaves intact the general rule that personal beliefs are not a license to deny equal service in mainstream businessesen.wikipedia.org.

-

Increase in Pre-Enforcement Challenges: One subtle but significant aspect of 303 Creative is the Court’s tolerance for a pre-enforcement lawsuit. Typically, a plaintiff must show a concrete injury or imminent threat. Here, Lorie Smith had not yet been punished under the law – indeed, she hadn’t even entered the wedding website business or been asked by a real same-sex couple for servicelawcommentary.comcbsnews.com. Nonetheless, the Court found her fear of enforcement credible and ripe for review. This could embolden more “proactive” lawsuits by businesses (or individuals) who object to laws on First Amendment grounds before any penalty occurs. Constitutional litigators might seize this precedent to file test cases without waiting for, say, a complaint or fine to materialize. It’s a reminder that the current Court, especially where free speech or religious claims are involved, may be more willing than ever to step in early and settle the issue. (Of course, any such case still needs careful factual stipulations to show a real intention to do the regulated act and a likely conflict with the lawen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org.)

-

Challenges for Compliance and Enforcement: State civil rights commissions and legislatures are now in a tricky spot. They must enforce anti-discrimination laws while carving out First Amendment exceptions. We may see states issuing guidance on what counts as expressive – for instance, a state might clarify that pure services like transportation, lodging, banking, etc., have no speech element and thus no exemptions, whereas it might tread more carefully in enforcing the law against, say, a freelance graphic designer. Enforcement agencies might also re-focus on clear cases of status-based refusal (e.g. “We don’t serve Muslims” posted on a shop door – which 303 Creative would not protect) and possibly hold off on borderline expressive cases until courts give more direction. For lawyers counseling businesses, the advice will likely be: know your state’s law and enforcement posture, and when in doubt, seek a compromise that honors both principles (for example, referrals – Lorie Smith, to her credit, said she would refer same-sex couples to other designers who would serve themen.wikipedia.org, an approach that, while not a legal defense, at least shows good faith and mitigates harm).

-

Further Court Battles on the Horizon: All sides agree on one thing – 303 Creative is not the final word, but the opening of a new chapter. Already, new lawsuits have been filed or dusted off to test how far this ruling goes. For instance, a case involving a wedding photographer in Virginia asserted a similar right to decline same-sex weddings, and in light of 303 Creative, such plaintiffs are more likely to prevail or secure favorable settlements. Conversely, advocates for LGBTQ rights and other protected groups might look for the “right case” to draw a line – perhaps a scenario where a business’s claim of expression is weak or pretextual, hoping for a narrowing decision. Lawyers on the defense side will need to show that their clients’ work is truly expressive and that their objection is sincerely about content, not identity (courts will be on the lookout for any sign of animus). On the flip side, lawyers challenging refusals will probe for inconsistency: Would this business really refuse anyone else requesting the same content? For example, if a bakery won’t do a cake with two grooms toppers for a gay couple, would it also refuse the same cake design if commissioned for, say, a film prop or an art exhibit? If not, that could undercut the “message-based” rationale.

In practical terms, LGBTQ consumers and civil rights lawyers face a new reality in some states: a small but meaningful subset of businesses may hang out “creative conscience” shingle, indicating they won’t produce certain expressive works (websites, photographs, invitations, etc.) for same-sex weddings or other activities they disapprove of. Over time, the market might adjust — inclusive businesses could advertise to fill the void, and discriminating providers might remain a niche. But as Justice Sotomayor observed, even symbolic denials of service inflict dignitary harmcbsnews.com, calling to mind an era when groups were told to use the other water fountain or stay out of certain establishments. The legal conversation post-303 Creative will revolve around where to draw the line between an artist’s freedom and a customer’s equality in that marketplace.

The Road Ahead: A Changing Legal Landscape

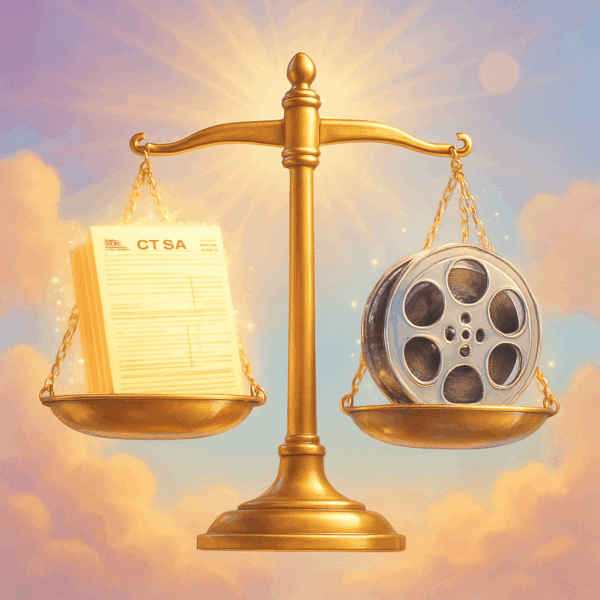

For those in the legal profession, 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis encapsulates the Supreme Court’s current trajectory: an aggressive defense of First Amendment freedoms, even at the expense of long-standing anti-discrimination principles. It resolves a key issue that Masterpiece Cakeshop punted on, and in doing so, it highlights the significance of the Court’s recent conservative super-majority. As observers noted, the outcome likely would have been different a decade ago – but today’s Court has shown a willingness to revisit and reshape constitutional balances in favor of individual speech and religious rights.

Constitutional law practitioners should view this ruling as both a tool and a warning. It’s a tool in that it provides robust precedent to deploy for clients who engage in expressive vocations and fear government compulsion. But it’s a warning that the Court is comfortable carving out exceptions to generally applicable laws when convinced a higher principle is at stake. This tension between free expression and equal protection will continue to generate difficult cases. As Justice Gorsuch wrote, 303 Creative does not give anyone a free pass to discriminate willy-nillyfordharrison.com – but exactly how its logic might be invoked in future conflicts (for example, a vendor refusing to serve an interracial wedding on “message” grounds, or a college student group excluding certain people from leadership citing expressive association) will be watched closely.

In the end, the 303 Creative case reminds us that constitutional law is not practiced in a vacuum. It affects real people and real businesses, sometimes in unexpected ways. A dispute that started with one web designer’s aspirations has now reset the legal playing field for wedding vendors, artists, and creative professionals nationwide. It challenges lawyers to think creatively (no pun intended) about how to reconcile two fundamental values: the freedom to speak (or not speak) one’s mind, and the right to participate in economic life without facing discrimination. Striking that balance is the work of a democratic society – and with this ruling, the Supreme Court has definitively tipped the scales toward the side of individual expression. How heavy that tip proves to be, and whether the other side can still hold firm on anti-discrimination ideals, will be the story to watch in the coming years.

Endnotes:

-

Supreme Court of the United States, 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis, 600 U.S. 570 (2023) – Holding: The First Amendment prohibits Colorado from forcing a website designer to create expressive designs speaking messages with which the designer disagreesscotusblog.com.

-

Amy Howe, “Supreme Court rules website designer can decline to create same-sex wedding websites,” SCOTUSblog (June 30, 2023) – Analysis of the decision: the 6–3 majority held that Colorado cannot compel the designer’s speech, a victory for business owners with religious objectionsscotusblog.comscotusblog.com. Sotomayor’s dissent called it “a sad day in American constitutional law,” warning it marks gays and lesbians as second-classscotusblog.comscotusblog.com. (SCOTUSblog is a reputable independent news source covering Supreme Court decisions.)

-

303 Creative LLC v. Elenis case page, SCOTUSblog – Summary of case details: argued Dec. 5, 2022; decided June 30, 2023; Justice Gorsuch authored the opinion, Justice Sotomayor dissented. Confirms that the majority was 6–3 and provides the syllabus quote on the First Amendment holdingscotusblog.comscotusblog.com.

-

FordHarrison LLP, “Navigating the U.S. Supreme Court’s Decision in 303 Creative LLC and its Implications” (Legal Alert, July 5, 2023) – Notes that the majority emphasized the ruling is not a blanket “license to discriminate.” The Court distinguished ordinary anti-bias laws (e.g., hiring, admissions) from this case, calling comparisons to racial segregation “pure fiction”fordharrison.com. It acknowledged prior cases upholding anti-discrimination laws (e.g., Hishon and Roberts v. Jaycees) remain untouched but said compelling speech is a different matterfordharrison.comfordharrison.com. The dissent, by contrast, placed the case in the civil-rights context and feared it will permit exclusion of groups, noting the majority avoids discussing Runyon v. McCrary (1976) which rejected a similar First Amendment claim by a segregated schoolfordharrison.com.

-

David Cole, “‘We Do No Such Thing’: 303 Creative v. Elenis and the Future of First Amendment Challenges to Public Accommodations Laws,” Yale Law Journal Forum (Jan. 29, 2024) – Argues that the decision’s parameters are actually narrow. Cole explains that the majority and dissent spoke past each other: the majority saw a compelled message that the state cannot force, while the dissent saw an unjustified denial of serviceyalelawjournal.orgyalelawjournal.org. He posits that properly understood, 303 Creative applies only when a business objects to a specific message for anyone (not refusing a customer’s identity) and when the state’s interest is merely to suppress an unpopular idea rather than ensure equal accessyalelawjournal.org. Under this view, the ruling should have “minimal impact” on most public accommodation lawsyalelawjournal.org, since in the vast majority of cases businesses do not have blanket content-based policies like Smith’s.

-

Christopher Hazlehurst, “Supreme Court Rules Religious Web Designer Can Refuse to Work on Same-Sex Weddings,” Law Commentary (July 5, 2023) – Provides a journalistic overview of the case and its unusual posture. Notes that the decision is controversial both for expanding religious objections and for being based on a hypothetical scenariolawcommentary.com. Describes Sotomayor’s dissent: “the Court, for the first time in its history, grants a business open to the public a constitutional right to refuse to serve members of a protected class.” The dissent argued CADA doesn’t compel any speech – Smith “remains free… to decide what messages to include or not to include” on her websites, she just can’t refuse the service to gay couples altogetherlawcommentary.comlawcommentary.com. The article also discusses the standing issue: Smith had not been asked by a real same-sex couple at the time of suit, raising questions about why the Court heard a case with no direct injury (the piece notes the Court’s majority was “unperturbed” by the lack of actual harm, content to proceed on hypotheticals)lawcommentary.comlawcommentary.com.

-

303 Creative LLC v. Elenis – Wikipedia article (last updated 2024) – Provides background and context: Lorie Smith received a purported request from “Stewart” for a same-sex wedding website that turned out to be likely fake, though this did not affect the legal outcomeen.wikipedia.org. Confirms that roughly half of U.S. states (22 plus D.C.) have public accommodation laws barring LGBTQ discriminationscotusblog.com. Summarizes the Tenth Circuit’s ruling (which had upheld the law under strict scrutiny, creating a circuit split)en.wikipedia.org. The “Impact” section cites reactions: free speech advocates (including religious liberty groups) celebrated the rulingen.wikipedia.org, while LGBTQ advocates saw it as a serious setbacken.wikipedia.org. Notably, it mentions legal experts’ differing views: e.g., civil-rights attorney Mary Bonauto called the ruling a “mixed bag” that likely only protects very unique, custom services, whereas Professor Katherine Franke said it was “sweeping,” using the First Amendment to override anti-discrimination laws broadlyen.wikipedia.org.

-

Melissa Quinn, “Supreme Court sides with designer opposed to making same-sex wedding websites in case over LGBTQ rights and free speech,” CBS News (June 30, 2023) – A news report on the decision. Includes key quotes from the opinions (e.g., Gorsuch: “If [Smith] wishes to speak, she must either speak as the State demands or face sanctions…”cbsnews.com; Sotomayor: “Today, the Court… grants a business open to the public a constitutional right to refuse to serve members of a protected class.”cbsnews.com). Describes the background: Smith has not made any wedding websites yet, but wanted to, and feared punishment under Colorado lawcbsnews.com. Notes the Tenth Circuit had found her product was “pure speech” but still ruled against her due to the state’s compelling interestcbsnews.com. Also provides context that this case is one of several post-Obergefell clashes between religious business owners and LGBTQ rights, referencing Masterpiece Cakeshop (2018) as a precursor that left the core issue unresolvedcbsnews.com. Includes President Biden’s response: “The Supreme Court’s disappointing decision… undermines that basic truth [of no discrimination], and painfully it comes during Pride month…”cbsnews.com.

-

Mark Satta, “303 Creative LLC v. Elenis (10th Circuit) (2021),” First Amendment Encyclopedia (mtsu.edu) – Explains the lower courts’ decisions. The Tenth Circuit in 2021 held that Colorado’s law did not violate Smith’s rights, even though making her create same-sex wedding sites did compel speech, because the law survived strict scrutiny by furthering a compelling interest in ensuring equal access and dignity for marginalized groupsfirstamendment.mtsu.edufirstamendment.mtsu.edu. It also noted that the law’s prohibition on Smith publishing her intent to discriminate (the “communication clause”) was only barring unlawful discriminatory advertisements, not suppressing her speech unjustlyfirstamendment.mtsu.edu. This entry provides useful insight into the arguments that almost carried the day below – that anti-discrimination laws can trump free speech in the commercial sphere due to the “unique evils” of segregation in the marketplacefordharrison.com. Chief Judge Tymkovich’s dissent at the 10th Circuit presaged Gorsuch’s opinion, warning that forcing Smith’s speech was “remarkable” and “novel” government coercionen.wikipedia.org.