How an unpublished Massachusetts opinion is quietly rewriting the rules of fiduciary warfare—and what every planner, litigator, and trustee should learn from the fallout.

The Day the Deed Changed Hands

On a gray December morning in 2011, Robert Rankin—long‑time family accountant and freshly minted successor trustee—signed a purchase‑and‑sale agreement with an unlikely counter‑party: himself. For $210,000 he snapped up Angela Gonzalez’s two‑family house in Quincy, Massachusetts, neatly financing the deal with cash he controlled as trustee. Six months earlier, an independent appraisal had pegged fair market value at $385,000. No email to beneficiaries, no court license, no outside valuation at closing. Just Rankin, a pen, and a fat conflict of interest.

Fast‑forward five years. Angela’s children, Juan and Marisol Gonzalez, sit in a packed courtroom watching the Appeals Court of Massachusetts rule on Gonzalez v. Rankin. What began as a family skirmish over a modest Cape Cod‑style duplex has morphed into a precedent‑shifting lesson in fiduciary liability—one that every trust lawyer should now have bookmarked.

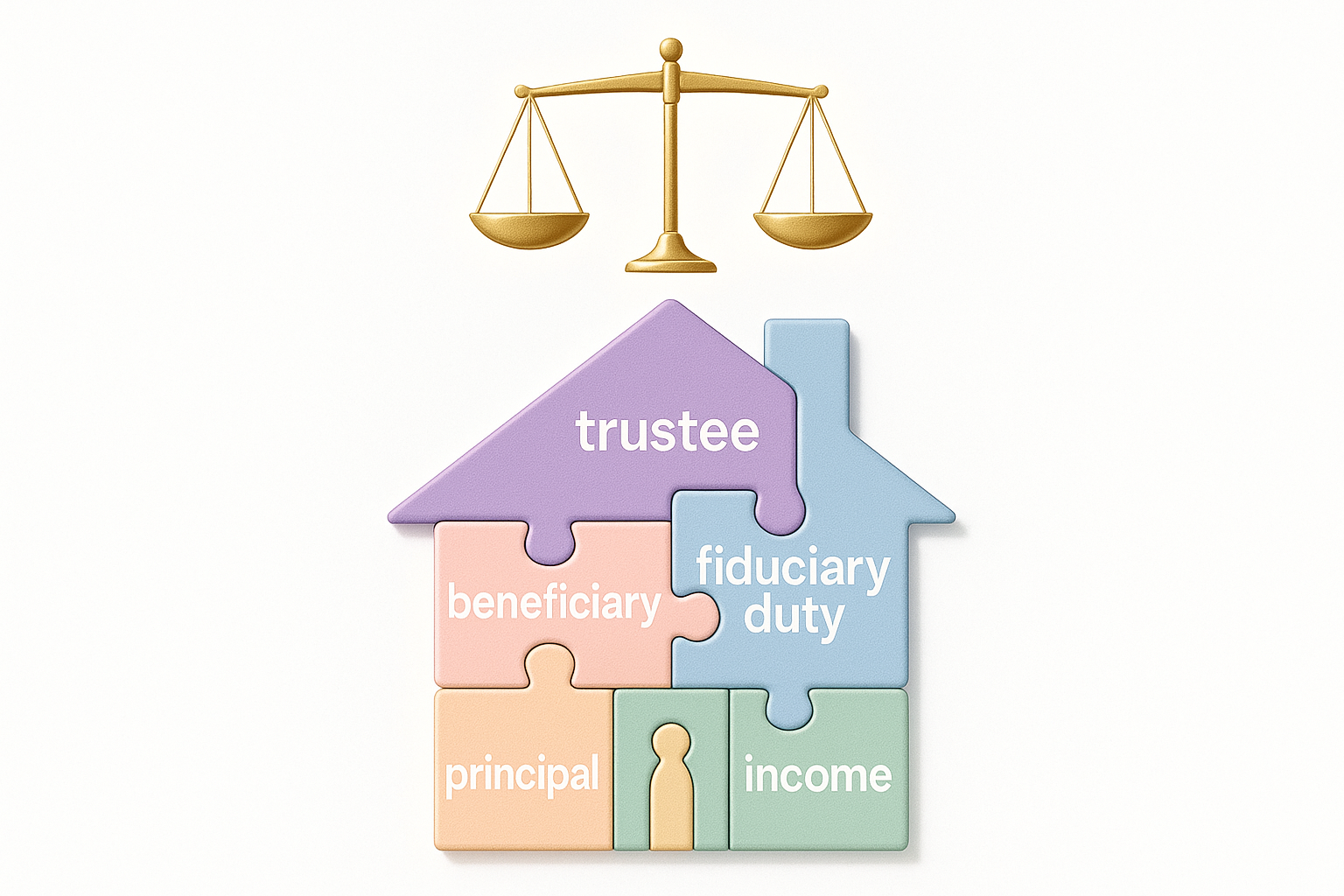

Visual Case Brief

| Snapshot | Detail |

|---|---|

| Citation | Gonzalez v. Rankin, No. 15‑P‑771, 2016 Mass. App. Unpub. LEXIS 432 (Apr 20 2016) |

| Lower Court | Norfolk Probate & Family Court—trustee removed; surcharge $82 k |

| Appeals Court | Removal affirmed; surcharge increased to $247 k; remanded for attorney fees |

| Key Statute | Mass. Uniform Trust Code (MUTC) §§ 706, 100, 1004 |

| Doctrinal Headline | “Highest intermediate value” measure of damages adopted for self‑dealing trustee who still owns the property |

The Breach Heard ’Round the Bar

At first glance, Gonzalez looks like garden‑variety fiduciary mischief: trustee buys trust property at a discount; beneficiaries cry foul. Yet three moves by the Appeals Court turned a fact‑bound family saga into a doctrinal earthquake:

-

One Bad Act = Removal

Under MUTC §706, the panel held that a single egregious act—here, self‑dealing without disclosure—was enough to oust the trustee. No pattern of misconduct required. -

The “Highest Intermediate Value” Rule

Because Rankin still owned the property, the court refused to limit damages to the delta between sale price and value on the closing date. Instead, it ordered him to restore the trust to the highest value the asset reached between breach and judgment. Translation: appreciation belongs to beneficiaries, not the breaching fiduciary. -

Automatic Fee‑Shifting

Leveraging equitable powers plus MUTC §1004, the panel made clear that beneficiaries who must sue to unwind trustee misconduct may recover their attorneys’ fees—no special showing of “bad faith” necessary once a serious breach is proven.

“A trustee who places himself on both sides of a bargain may not profit by hindsight. Equity demands restoration of what the trust would have held, not what it happened to hold.” —Gonzalez v. Rankin (unpublished order)

Why This Matters Beyond Quincy

Gonzalez is unpublished under Massachusetts Rule 1:28, meaning it lacks formal precedential weight. But in practice, probate judges and fiduciary‑litigation specialists cite 1:28 decisions every day for their persuasive value. And Gonzalez plugs a conspicuous hole: before 2016, Bay State courts had offered only scattered guidance on calculating trustee surcharge. By importing the Restatement (Third) of Trusts §100’s appreciation‑damages rubric, the panel vaulted Massachusetts to the front of the beneficiary‑protection pack.

For planners, the reverberations are immediate:

-

Drafting realty trusts? Build bright‑line consent or court‑license requirements for insider transactions.

-

Serving as trustee? Disclose everything, obtain independent valuations, and document beneficiary approval in writing.

-

Litigating a surcharge claim? Plead both disgorgement of profits and highest‑value damages—Gonzalez blesses the double‑barreled ask.

Table 1 Damage Scenarios After Gonzalez

| Scenario | Pre‑Gonzalez Likely Recovery | Post‑Gonzalez Recovery |

|---|---|---|

| Trustee sells asset to self, immediately flips at profit | Sale‑date FMV – insider price | Greater of: • Highest value between sale and judgment, or • Trustee’s actual profit |

| Trustee retains asset (no flip) and it appreciates | Difference at closing, possibly zero | Appreciation up to judgment date—even if market did the trustee a favor |

| Trustee commingles cash, no proof of loss | Often nominal damages | Tracing + disgorgement of any investment gains |

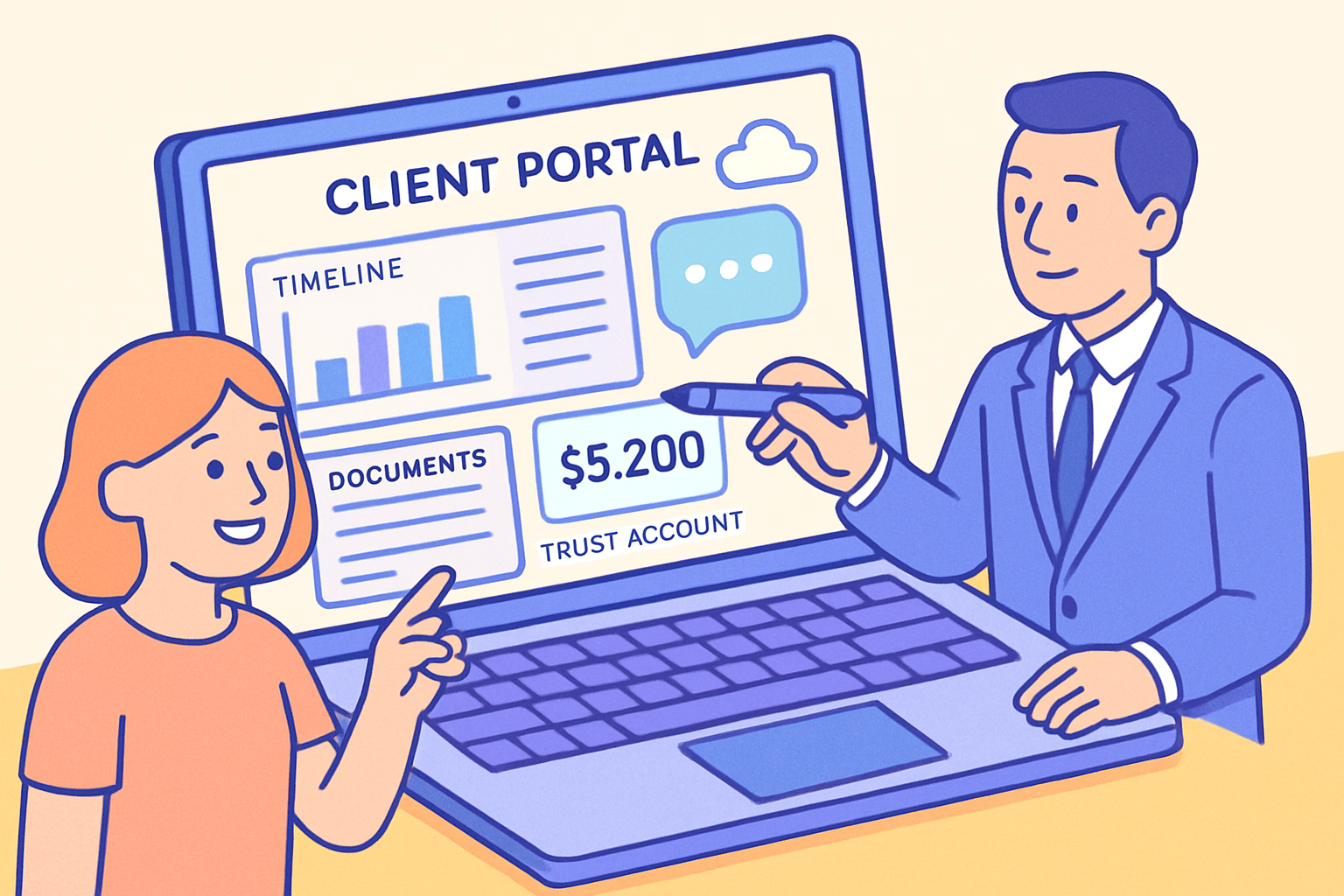

The Take‑Home for Tech‑Savvy Fiduciaries

Gonzalez reads like a cautionary tale for the digital age. Rankin’s undoing wasn’t a smoking gun email—it was a bland check register showing commingled funds and skipped appraisals. In an era of blockchain deed registries and AI‑driven compliance tools, trustees who still treat record‑keeping as an afterthought are playing with live voltage.

Three practical hacks:

-

Automated Valuation Alerts – Use prop‑tech APIs to flag when trust realty deviates more than 10 percent from recorded FMV.

-

Consent‑Capture Apps – Secure e‑signatures from beneficiaries before insider transactions; PDF the packet straight to the trust file.

-

Shadow Ledgering – Maintain parallel audit‑trail ledgers (think read‑only blockchain) to demonstrate zero commingling.

Because when the subpoenas land, screenshots speak louder than affidavits.

Final Word

Angela Gonzalez’s old duplex may never grace an Architectural Digest spread, but the appellate order it spawned is already reshaping fiduciary risk calculus across Massachusetts—and filtering into CLE decks nationwide. Ignore it at your peril. Embrace its lessons, and you may just keep the keys to the family home and your professional license.

Endnotes

-

Gonzalez v. Rankin, No. 15‑P‑771, 2016 Mass. App. Unpub. LEXIS 432 (Mass. App. Ct. Apr. 20 2016).

-

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 203E §§ 706(b)(1), 706(b)(5), 813, 100, 1004 (Massachusetts Uniform Trust Code).

-

Restatement (Third) of Trusts §100(2) & §93 cmt. f (Am. L. Inst. 2012).

-

Pfannenstiehl v. Pfannenstiehl, 475 Mass. 105 (2016).

-

Caffrey v. U.S. Trust, No. 15‑P‑170, 2016 Mass. App. Unpub. LEXIS 454 (Apr. 13 2016).

-

Heystek v. Duncan, No. 15‑P‑922, 2016 Mass. App. Unpub. LEXIS 1113 (Oct. 24 2016).