By TheOneLawFirm.com Contributors

“It’s like a portal opened. Suddenly, Pennsylvania could be the courtroom for any claim against any company, anywhere.”

—Constitutional litigator reacting to Mallory v. Norfolk Southern Railway Co.

It started with cancer. It ended with a revolution in civil procedure.

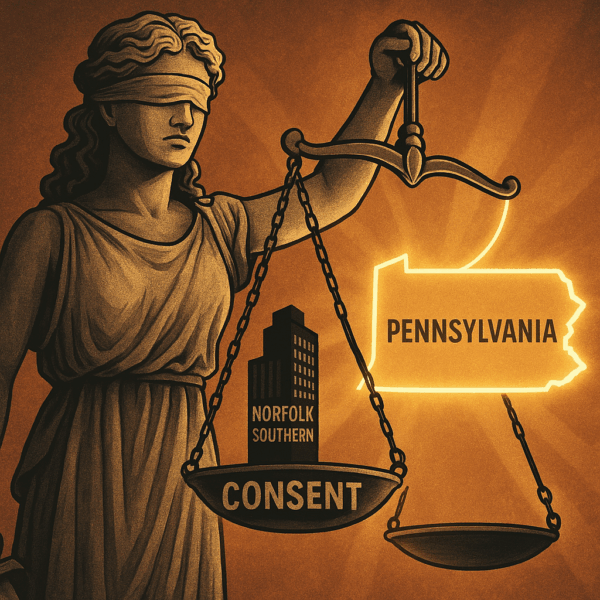

When Robert Mallory, a Virginia man and former railroad worker, was diagnosed with colon cancer, he pointed the finger squarely at his longtime employer, Norfolk Southern Railway Co. But instead of filing suit in his home state—or even in Georgia, where the company is headquartered—he took his case to Pennsylvania.

The reason? A long-forgotten piece of jurisdictional machinery: a state law that says if your company registers to do business in Pennsylvania, you automatically agree to be sued there. For anything. By anyone.

That obscure rule, buried in Pennsylvania’s corporate registration statutes, became the centerpiece of Mallory v. Norfolk Southern Railway Co., a U.S. Supreme Court case that cracked open the traditional boundaries of personal jurisdiction—and signaled a seismic shift for constitutional law and corporate litigation across the country.

A Blast from the Legal Past

To understand Mallory, you have to rewind more than a century.

In the early 1900s, before airplanes and the internet, courts relied on a simpler notion of power: If you came into our state, we can sue you. In 1917, the Supreme Court upheld a Missouri law saying that an insurance company, by registering to do business there, had consented to general jurisdiction. That case—Pennsylvania Fire—sat on the shelf for decades.

Then came International Shoe Co. v. Washington (1945), which ushered in a more nuanced approach: a defendant had to have “minimum contacts” with the forum state for jurisdiction to be fair. And in recent years, the Court doubled down, narrowing general jurisdiction to a company’s “home” (where it’s incorporated or headquartered) unless there was a specific, related reason to sue in a state.

So when Norfolk Southern argued that it couldn’t be sued in Pennsylvania for a Virginia-based cancer claim, most thought the case would be dismissed. And it was—until the U.S. Supreme Court rewrote the rules in June 2023.

Visual Case Brief: Mallory v. Norfolk Southern Railway Co. (2023)

| Case Name | Mallory v. Norfolk Southern Ry. Co., 600 U.S. 122 (2023) |

|---|---|

| Issue | Can a state require out-of-state corporations to consent to general jurisdiction as a condition of doing business? |

| Holding | Yes. The Court held that Pennsylvania’s statute did not violate due process. |

| Majority Opinion | Justice Gorsuch (joined by Thomas, Sotomayor, Jackson, and in part by Alito) |

| Key Precedent Cited | Pennsylvania Fire Insurance Co. v. Gold Issue Mining (1917) |

| Legal Impact | Revived consent-by-registration theory of personal jurisdiction. Opens path for more forum shopping. |

| Potential Challenges Ahead | Dormant Commerce Clause challenges; varying state interpretations |

The Consent Clause Heard ‘Round the Country

In a 5–4 ruling, the Court held that Norfolk Southern’s registration in Pennsylvania amounted to valid consent to general personal jurisdiction. Justice Gorsuch, writing for the majority, declared that Pennsylvania Fire was still good law. International Shoe, he said, didn’t erase earlier jurisdictional paths—it merely added new ones.

In essence, the Court said: Consent trumps contacts.

Justice Jackson drove the point home: personal jurisdiction is a right, not a mandate. And like most rights, it can be waived. Norfolk Southern, by registering to do business in Pennsylvania, had done exactly that—even if Pennsylvania’s statute forced their hand.

Dissenting Voices and the Federalism Alarm

But not everyone was convinced. Justice Barrett’s dissent warned that this decision obliterated the careful limits the Court had spent 80 years building.

“If every state can do what Pennsylvania just did,” she argued, “then national corporations could be sued anywhere, for anything. That’s not fair—it’s chaos.”

The fear? A world where every business is open to lawsuits in every state it registers in, regardless of where the injury occurred or whether the forum has any real stake in the dispute.

State Courts React: A Jurisdictional Patchwork

State Courts React: A Jurisdictional Patchwork

Since Mallory, courts around the country have begun testing the waters. Early signs suggest that states without explicit consent statutes are resisting its reach.

In Missouri and Mississippi, courts have declined to adopt Mallory‘s logic, pointing to the lack of clear legislative language. Utah, among others, even has statutes explicitly stating that registration does not equal jurisdiction.

This creates a messy national map. Some states now operate as potential litigation magnets. Others remain closed. The result? A high-stakes forum-shopping game for plaintiffs—and a strategic minefield for defense counsel.

Ripple Effects for Business and the Constitution

From a constitutional perspective, Mallory doesn’t just revive an old doctrine—it reshapes the balance of power between states and corporations. It reaffirms that states can impose significant legal consequences on out-of-state businesses, so long as the rules are clear and the business “consents.”

But there’s a twist. Justice Alito, who provided the crucial fifth vote, signaled that future cases might be decided not under the Due Process Clause—but under the Dormant Commerce Clause. If Pennsylvania’s law burdens interstate commerce too much, it could still be struck down.

In other words, Mallory won the battle, but the war over jurisdiction might not be over.

What This Means for Constitutional Litigators

For those practicing in constitutional law and civil procedure:

-

Expect new Dormant Commerce Clause challenges. These could shift the debate from personal fairness to economic regulation.

-

Reassess forum strategies. Consent-by-registration is now a viable anchor for jurisdiction—but only in some states.

-

Watch the states. New statutes may emerge, either emulating or resisting Pennsylvania’s model.

-

Educate clients. Especially national businesses who now face the risk of being sued in any state where they’re registered.

Final Verdict: The Past is Prologue

Mallory didn’t just revive a forgotten precedent—it ignited a constitutional debate about where companies can be sued and who gets to decide.

For litigators, it’s a new age of jurisdiction. For constitutional scholars, it’s a return to fundamentals. For corporations? It’s time to study your state registrations very, very carefully.

Endnotes

-

Mallory v. Norfolk Southern Railway Co., 600 U.S. 122 (2023).

-

Pennsylvania Fire Insurance Co. v. Gold Issue Mining & Milling Co., 243 U.S. 93 (1917).

-

International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310 (1945).

-

Daimler AG v. Bauman, 571 U.S. 117 (2014).

-

Justice Barrett, dissenting opinion in Mallory, 600 U.S. at 162.

-

Justice Alito, concurring in part and in judgment, Mallory, 600 U.S. at 176.

-

Harvard Law Review, “Consent Reimagined: Mallory’s Jurisdictional Revival,” 137 Harv. L. Rev. 360 (2023).

-

Sidley Austin LLP, “Corporate Personal Jurisdiction After Mallory,” Litigation Insight Report, July 2023.

-

Drug & Device Law Blog, “Mallory in the States: One Year Later,” June 2024.

-

Utah Code § 16-17-203(2) (disavowing general jurisdiction by registration).