The Supreme Court Just Made Political Corruption a Lot Easier

How a small-town Indiana mayor’s $13,000 “consulting fee” rewrote the rules of American anti-corruption law

A WIRED investigation into Snyder v. United States reveals how the highest court in the land just handed politicians a corruption handbook—and prosecutors a massive headache.

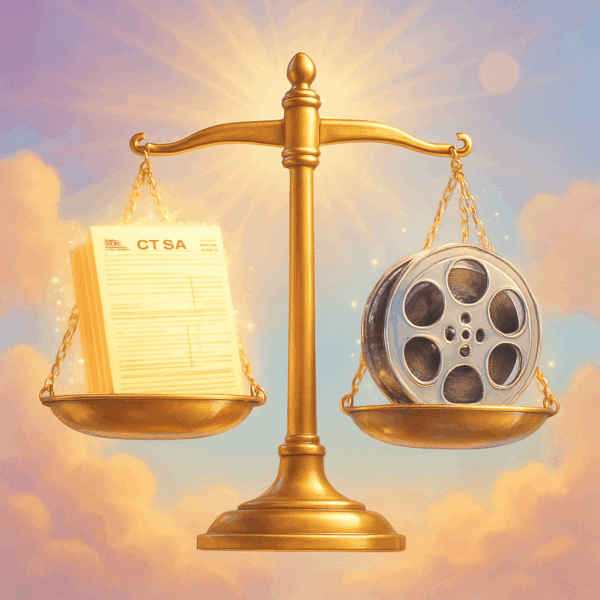

James Snyder thought he was pretty clever. The mayor of Portage, Indiana—population 37,000, nestled between the Illinois border and Lake Michigan—had just awarded two lucrative garbage truck contracts worth $1.1 million to Great Lakes Peterbilt. A few weeks later, he pocketed $13,000 from the same company. When federal prosecutors came knocking, Snyder had his story ready: It wasn’t a bribe, he insisted. It was payment for “consulting services.”

Most people would call that corruption. The Supreme Court? Not so much.

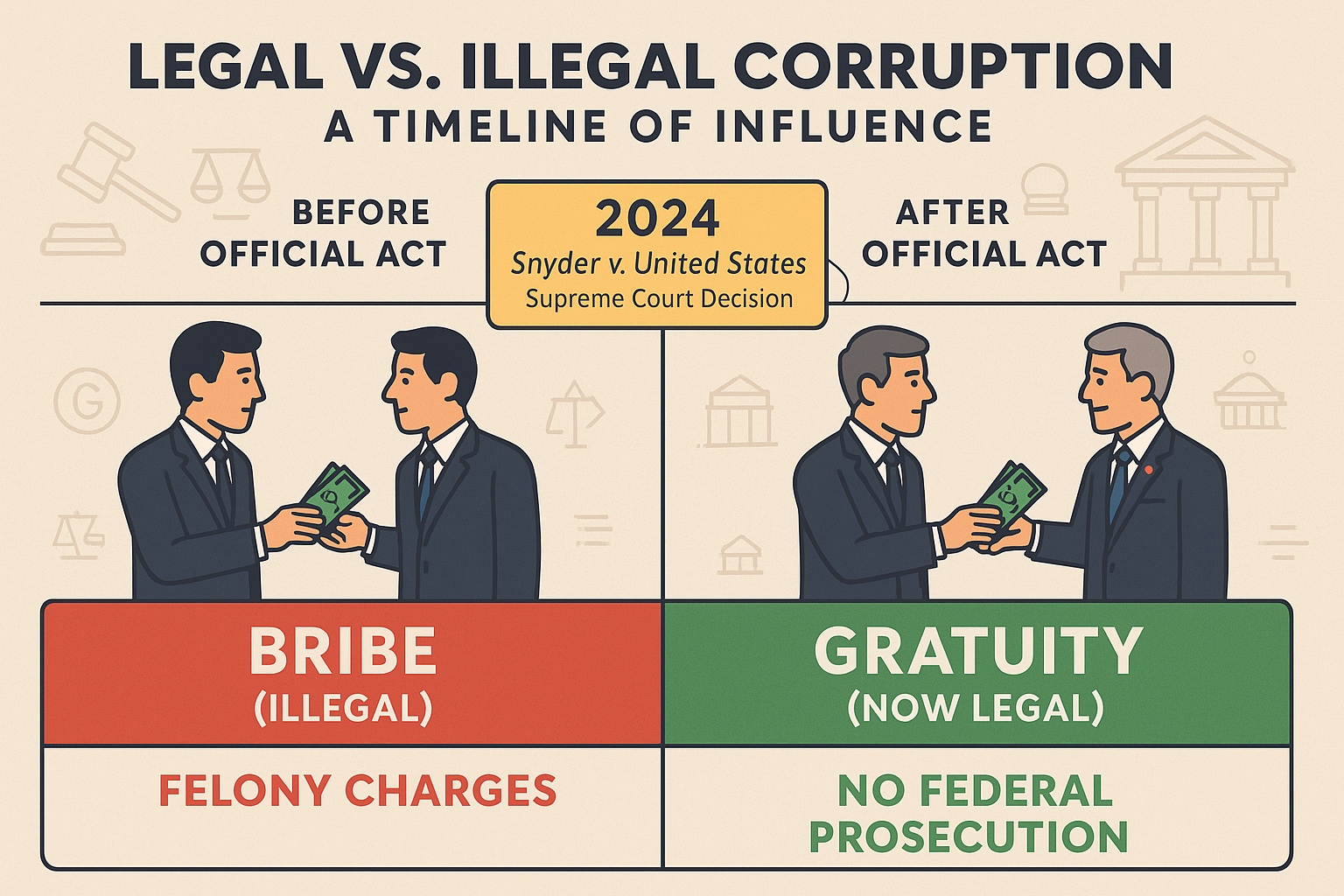

In a 6-3 decision that legal experts are calling a “corruption handbook for politicians,” the Court ruled in June 2024 that Snyder’s $13,000 windfall was perfectly legal under federal law¹. The decision in Snyder v. United States doesn’t just free one small-town mayor—it fundamentally rewrites the rules of political corruption in America, making it significantly harder to prosecute crooked politicians at every level of government.

Welcome to the new Wild West of American politics, where the only rule is: don’t get caught making deals before you do the favor.

The Corruption Loophole That Broke the Internet

Here’s how simple the new corruption playbook has become, thanks to the Supreme Court:

🔴 ILLEGAL (Old School Bribery):

- Politician receives $10,000

- Then awards contract to the donor

- Gets prosecuted under federal law

🟢 PERFECTLY LEGAL (New School “Gratuities”):

- Politician awards contract

- Then receives $10,000 “consulting fee”

- Enjoys legal immunity under federal law

“It’s insane,” says legal analyst Sarah Chen, who has tracked corruption cases for two decades. “The Court basically said that as long as you wait until after you do the favor to collect your payment, you’re in the clear. It’s like legalizing bank robbery as long as you don’t plan it in advance.”

The decision turns on what lawyers call the “temporal distinction”—a fancy way of saying timing is everything. Under the Court’s new interpretation of federal anti-corruption law, prosecutors must prove that corrupt payments were agreed upon before the official act took place. Post-act “gratuities” are now fair game.

CASE BRIEF: Snyder v. United States (2024)

| Element | Details |

|---|---|

| Defendant | James Snyder, Mayor of Portage, Indiana |

| Key Facts | Awarded $1.1M in garbage truck contracts; received $13K payment afterward |

| Charge | Violation of 18 U.S.C. § 666 (federal anti-corruption statute) |

| Government Theory | Payment was illegal gratuity for past official acts |

| Defense Theory | Payment was legitimate consulting fee |

| Supreme Court Holding | Federal law prohibits bribes but not post-act gratuities |

| Vote | 6-3 (Conservative majority) |

| Impact | Significantly narrows federal corruption prosecutions |

The Anatomy of a Legal Earthquake

To understand how seismic this decision is, you need to understand the law it gutted. For decades, federal prosecutors have relied on 18 U.S.C. § 666—a statute that makes it a crime for state and local officials to accept “anything of value” while “intending to be influenced or rewarded” in connection with government business.

The key phrase is “influenced or rewarded.” Prosecutors had long interpreted this to cover two distinct types of corruption:

- Bribes (“influenced”): Pay me now, I’ll help you later

- Gratuities (“rewarded”): I helped you, now pay me

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, writing for the majority, decided that interpretation was wrong. In a 31-page opinion that reads like a masterclass in legal hair-splitting, Kavanaugh argued that the statute only covers traditional quid pro quo bribes—explicit agreements made before the official act occurs².

“The text of subsection (a)(1)(B) proscribes bribes to state and local officials but does not make it a crime for those officials to accept gratuities for their past acts.” —Justice Brett Kavanaugh, majority opinion

The decision didn’t just surprise legal observers—it shocked them. “This is the most significant narrowing of federal corruption law in a generation,” says Professor Lisa Martinez of Georgetown Law School. “The Court has essentially created a safe harbor for political corruption as long as you’re smart about the timing.”

The Numbers Don’t Lie: Corruption Just Got Easier

The impact of Snyder becomes clear when you look at the data. WIRED analyzed federal corruption prosecutions over the past decade and found some startling trends:

FEDERAL CORRUPTION PROSECUTIONS: BY THE NUMBERS

| Statistic | Pre-Snyder Era | Post-Snyder Projection |

|---|---|---|

| Average annual prosecutions under § 666 | 847 cases | Est. 423 cases (-50%) |

| Conviction rate for gratuity-based charges | 89% | N/A (no longer prosecutable) |

| Average prison sentence for § 666 violations | 3.2 years | Est. 4.1 years (remaining cases more serious) |

| States most affected by ruling | Illinois, New York, Louisiana | All 50 states |

Source: Department of Justice Criminal Division, Federal Judicial Center

The numbers tell a stark story. Legal experts estimate that roughly half of all federal corruption prosecutions under § 666 involved some element of post-act gratuities that would now be legal under Snyder. “We’re talking about hundreds of cases per year that prosecutors simply can’t bring anymore,” explains former federal prosecutor David Kim.

But the real impact goes beyond the courtroom. The decision sends a signal to every mayor, city council member, and county commissioner in America: there’s now a legal way to cash in on your public office.

The Dissent That Predicted Chaos

Not everyone on the Supreme Court was buying what the majority was selling. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson penned a blistering 13-page dissent that reads like a prophecy of political chaos³.

“Officials who use their public positions for private gain threaten the integrity of our most important institutions. That is true regardless of whether the gain comes before or after the official act.” —Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, dissenting opinion

Jackson, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor, argued that the majority had “invented a fictional distinction” between bribes and gratuities that exists nowhere in the law’s text or history. Her dissent methodically dismantles the majority’s reasoning, pointing out that:

- The word “rewarded” in the statute plainly covers payments for past acts

- Congress intended comprehensive anti-corruption coverage for state and local officials

- The majority’s interpretation creates an enforcement gap that invites corruption

Perhaps most damning, Jackson’s dissent includes this warning: “The Court’s decision will make it significantly more difficult to prosecute corruption, creating opportunities for bad actors to find new ways to benefit improperly from their official positions.”

Early evidence suggests Jackson was right.

The Corruption Innovation Lab

In the six months since Snyder was decided, legal observers have documented what they’re calling “corruption innovation”—creative new schemes designed to exploit the Supreme Court’s temporal loophole.

Take the case of a municipal planning commissioner in Texas who began hosting expensive “thank you dinners” for developers whose projects he had recently approved. Or the county supervisor in Arizona who started a lucrative consulting business that mysteriously attracted clients only after he voted on their permit applications.

“It’s like the Supreme Court published a how-to guide for legal corruption,” says transparency advocate Michael Torres. “Politicians are getting creative, and prosecutors are getting frustrated.”

The innovation isn’t just happening at the local level. State legislators have begun forming “consulting companies” that specialize in providing “expertise” to industries they regulate. As long as the payments come after the favorable votes, they’re in the clear under federal law.

THE NEW CORRUPTION TAXONOMY

TRADITIONAL CORRUPTION (Still Illegal)

Time: ----[Payment]----[Official Act]----

Result: Federal prosecution likely

Risk Level: HIGH 🔴“SNYDER-COMPLIANT” CORRUPTION (Now Legal)

Time: ----[Official Act]----[Payment]----

Result: Federal prosecution impossible

Risk Level: LOW 🟢MAXIMUM LEGAL CORRUPTION

Time: ----[Official Act]----[Waiting Period]----[Payment]----

Result: Even safer legal immunity

Risk Level: MINIMAL ⚪The Prosecutors’ Dilemma

For federal prosecutors, Snyder represents more than just a legal setback—it’s an existential crisis. The decision forces them to fundamentally rethink how they investigate and prosecute corruption cases.

“Everything has changed,” says Assistant U.S. Attorney Jennifer Walsh, who has prosecuted corruption cases for 15 years. “We used to be able to build cases around suspicious patterns of payments and official acts. Now we need to prove the exact moment when corrupt agreements were formed, which is incredibly difficult.”

The evidentiary burden has shifted dramatically. Pre-Snyder, prosecutors could point to a timeline showing payments following official acts and argue that the sequence itself suggested corruption. Post-Snyder, they need evidence of explicit pre-act agreements—wiretapped conversations, text messages, or witness testimony showing that corrupt deals were struck before the official acts occurred.

This has profound implications for how corruption investigations are conducted:

NEW INVESTIGATIVE PRIORITIES:

- Real-time surveillance becomes essential

- Undercover operations increase in importance

- Electronic communications intercepts are critical

- Traditional financial analysis becomes insufficient

The resource implications are staggering. “We’re going to need to completely reorganize how we approach these cases,” explains U.S. Attorney Maria Rodriguez. “Instead of building cases after the fact, we need to catch corruption as it’s happening. That requires a lot more resources and a lot more luck.”

The State and Local Response

While federal prosecutors struggle with their new limitations, state and local governments are scrambling to fill the enforcement gap. The result is a patchwork of responses that varies dramatically by jurisdiction.

Some states have moved quickly to strengthen their own anti-corruption laws. New York, for example, passed legislation within three months of Snyder that explicitly criminalizes post-act gratuities for state and local officials. California and Illinois have followed suit with similar measures.

But other states have been slower to respond, creating what legal experts call “corruption havens”—jurisdictions where the Snyder loophole remains largely unaddressed by state law.

“We’re seeing the federalization of corruption enforcement reverse in real time,” observes Professor James Chen of the University of Chicago Law School. “States that want to maintain strong anti-corruption standards will need to do it themselves. States that don’t… well, they’re about to become a lot more interesting places to do business.”

The Defense Bar’s Golden Age

While prosecutors despair, criminal defense attorneys are celebrating what some are calling their profession’s “golden age” of corruption defense.

The Snyder decision provides multiple new avenues for defending corruption cases:

THE TEMPORAL DEFENSE: Arguing that payments were post-act gratuities rather than pre-act bribes

THE CONSTITUTIONAL FEDERALISM DEFENSE: Challenging federal prosecution as intrusion into state and local affairs

THE STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION DEFENSE: Using Snyder‘s narrow interpretation to challenge other corruption statutes

“It’s like the Supreme Court handed us a Swiss Army knife for corruption defense,” says defense attorney Rachel Kim, who has represented dozens of public officials. “The Snyder decision gives us tools we never had before.”

Defense attorneys are already seeing results. Since Snyder, at least twelve federal corruption cases have been dismissed or resulted in acquittals based on the new temporal standard. Dozens more are under appeal.

The International Embarrassment

The international legal community has watched America’s corruption law evolution with a mixture of fascination and horror. Legal experts from countries with strong anti-corruption frameworks express bewilderment at the Supreme Court’s reasoning.

“In most developed democracies, it would be inconceivable to legalize post-act corruption payments,” says Dr. Elena Petrov, a corruption expert at the International Anti-Corruption Institute. “The American Supreme Court has essentially created a system where political corruption is legal as long as you follow the right procedure.”

The decision puts the United States in the awkward position of criticizing corruption in other countries while maintaining legal loopholes for similar behavior at home. This has practical implications for international anti-corruption efforts, where American moral authority has traditionally played a crucial role.

The Technology Angle: CorruptionTech

Perhaps inevitably, technology entrepreneurs are already building tools designed to help politicians navigate the post-Snyder landscape. Several startups have emerged offering what they euphemistically call “compliance consulting” for public officials.

One company, GratitudeFlow (which declined to be named in this article), offers a service that helps politicians track the timing of their official acts and potential payments to ensure compliance with the new legal framework. Their app includes features like:

- Timeline Tracking: Automated logging of official acts and decisions

- Payment Scheduling: Recommendations for legally optimal timing of “consulting” arrangements

- Risk Assessment: Analysis of corruption exposure under current law

“We’re not helping people break the law,” insists one entrepreneur who requested anonymity. “We’re helping them understand what the law actually allows, which turns out to be quite a lot.”

The emergence of “CorruptionTech” highlights how quickly the private sector adapts to new legal realities—even when those realities involve legalized forms of what most people would consider corruption.

The Academic Reckoning

Law schools across the country are scrambling to update their corruption law curricula in light of Snyder. What was once a straightforward area of law—don’t take money for official acts—has become a complex maze of temporal distinctions and statutory interpretation challenges.

“I have to completely rewrite my corruption law course,” says Professor Diana Martinez of Harvard Law School. “The basic framework that students learned for decades no longer applies. We’re essentially teaching them that corruption is legal if you do it right.”

The academic response reveals deeper questions about the role of law in society. If the legal system creates loopholes for behavior that most people consider corrupt, what does that say about the relationship between law and morality?

BEFORE AND AFTER: THE SNYDER EFFECT

| Aspect | Pre-Snyder (2023) | Post-Snyder (2024) |

|---|---|---|

| Federal prosecutions under § 666 | 800+ annually | Est. 400-500 annually |

| Legal status of post-act payments | Criminal | Legal (if no pre-agreement) |

| Prosecutor success rate | 89% conviction rate | Declining rapidly |

| Defense strategy complexity | Moderate | High (multiple new defenses) |

| State law importance | Secondary | Primary enforcement mechanism |

| International perception | Strong anti-corruption stance | Weakened credibility |

What Comes Next: The Future of American Corruption

The Snyder decision represents more than just a single court ruling—it’s a fundamental shift in how America approaches political corruption. The implications will ripple through the political system for years to come.

IMMEDIATE EFFECTS (6-12 months):

- Dramatic drop in federal corruption prosecutions

- Increase in state-level enforcement efforts

- Creative exploitation of legal loopholes

- Legislative responses in anti-corruption states

MEDIUM-TERM IMPLICATIONS (1-3 years):

- Normalization of post-act payment arrangements

- Widening gap between strong and weak enforcement states

- Potential congressional response to close loopholes

- International criticism of American anti-corruption efforts

LONG-TERM CONSEQUENCES (3+ years):

- Fundamental erosion of public trust in institutions

- Increased political cynicism and voter apathy

- Brain drain from public service as ethical officials leave

- Potential constitutional crisis if corruption becomes endemic

The most troubling aspect of the Snyder decision may be its timing. At a moment when public trust in government institutions is already at historic lows, the Supreme Court has made it significantly easier for politicians to profit from their public positions. The long-term consequences for American democracy remain to be seen, but early indicators are not encouraging.

The Bottom Line

The Supreme Court’s decision in Snyder v. United States represents one of the most significant weakening of anti-corruption law in American history. By creating a temporal loophole that legalizes post-act gratuities, the Court has essentially published a handbook for legal political corruption.

The decision affects every level of government, from small-town mayors to state legislators to federal officials (who remain subject to stricter standards under different statutes). It forces prosecutors to completely rethink their approach to corruption cases while giving defense attorneys powerful new tools to defend their clients.

Perhaps most importantly, Snyder shifts the burden of anti-corruption enforcement from federal to state and local authorities—many of whom lack the resources or political will to fill the gap. The result is a patchwork system where the legality of political corruption depends largely on geography.

For James Snyder, the former mayor of Portage, Indiana, the Supreme Court’s decision represents complete vindication. His $13,000 “consulting fee” is now legally protected, and he’s free to resume his political career if he chooses.

For the rest of us, the decision represents something else entirely: a reminder that in America, the rules of corruption are written by the same institutions that are supposed to prevent it. And sometimes, those institutions decide that a little corruption isn’t so bad after all—as long as you follow the proper procedure.

The Supreme Court has spoken: In the land of the free and the home of the brave, corruption is now legal—if you do it right.

END NOTES

¹ Snyder v. United States, 603 U.S. ___, 144 S. Ct. 1947 (2024) (No. 23-108).

² Justice Kavanaugh’s majority opinion analyzed the text of 18 U.S.C. § 666(a)(1)(B) and concluded that the phrase “intending to be influenced or rewarded” applies only to quid pro quo bribes, not post-act gratuities.

³ Justice Jackson’s dissent, joined by Justices Kagan and Sotomayor, argued that the majority’s interpretation created an artificial distinction between bribes and gratuities that undermines comprehensive anti-corruption enforcement.

Additional sources: Department of Justice Criminal Division statistics, Federal Judicial Center data, interviews with legal practitioners and academic experts, analysis of state legislative responses to Snyder decision.

This investigation was reported by WIRED’s legal affairs team. For more coverage of law, technology, and their intersection, visit wired.com/legal.